Evolution Benefits The Thieves

A sneaky sea slug repurposes the chloroplasts it takes from its algae prey.

Introduction

At the edges of our coasts, in rocky, shallow pools, a whole world waits to be discovered. As the tides flood in and out, they give rise to an environment that holds just a mere sampling of the remarkable diversity living in Earth’s oceans. Look past the large sea stars, anemones, and seaweeds, though, and focus on the tiny marine invertebrates gliding through the tide pool. One of these–an unassuming, frilly green sea slug that looks somewhat like a swimming rug–harbors a fascinating secret: it’s a thief. Its target? The cells that generate energy in its algae prey, also known as chloroplasts.

But wait–how can an animal steal cells from another organism, much less incorporate those cells into its own physiology? The answer to this question lies within the concept of symbiosis. When you think of symbiosis, you probably think of mutualism: two organisms in a partnership that they both benefit from. Examples of mutualism are rife across the animal kingdom and span all kinds of organisms and environments–from honey bees feeding and pollinating flowers to clownfish and the anemones they live in and protect. Symbiosis, however, encapsulates more than just the positive relationships; it also covers a wide range of negative or one-sided relationships, such as parasitism. Organisms can weaponize these partnerships in a variety of ways, whether by tricking their partner into a harmful symbiosis or by stealing something from them and repurposing it.

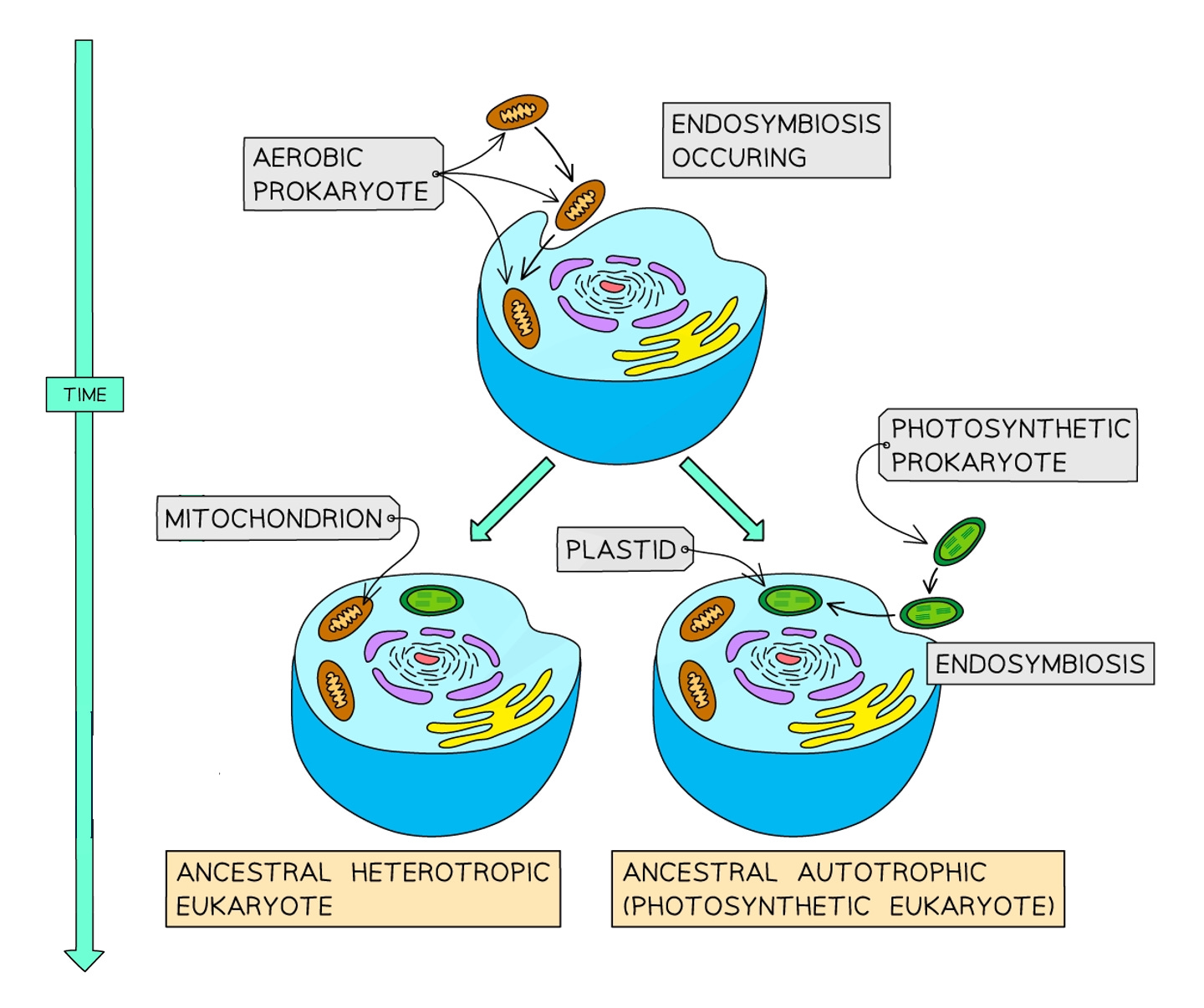

This concept of theft isn’t new, and it has actually played a role in evolution via a specific kind of symbiosis called endosymbiosis. Chances are that you’re probably more familiar with endosymbiosis than you might think–an example of it lives in your very own cells. The mitochondria, (or the powerhouse of the cell, as it’s affectionately known in biology classrooms), wasn’t always an organelle characteristic of animal cells. Approximately 1.5 billion or so years ago, when eukaryotes–cells with a nucleus–were still single-celled organisms meandering through Earth’s toxic oceans, they fatefully engulfed free-roaming bacteria. Over the course of evolution, this engulfment eventually became a partnership, giving rise to mitochondria and the animal cells that make up our own bodies in the present.

When Harvard biologist Nicholas Bellono and his team stumbled upon this phenomenon in Elysia crispata, better known as the lettuce slug, they wondered: was this the start of a new endosymbiosis between sea slugs and algal chloroplasts? And, if so, what strategies were these organisms using to harbor and incorporate these cells into their bodies? Lastly, did this incorporation confer advantages to the sea slug over other species?

Main Findings

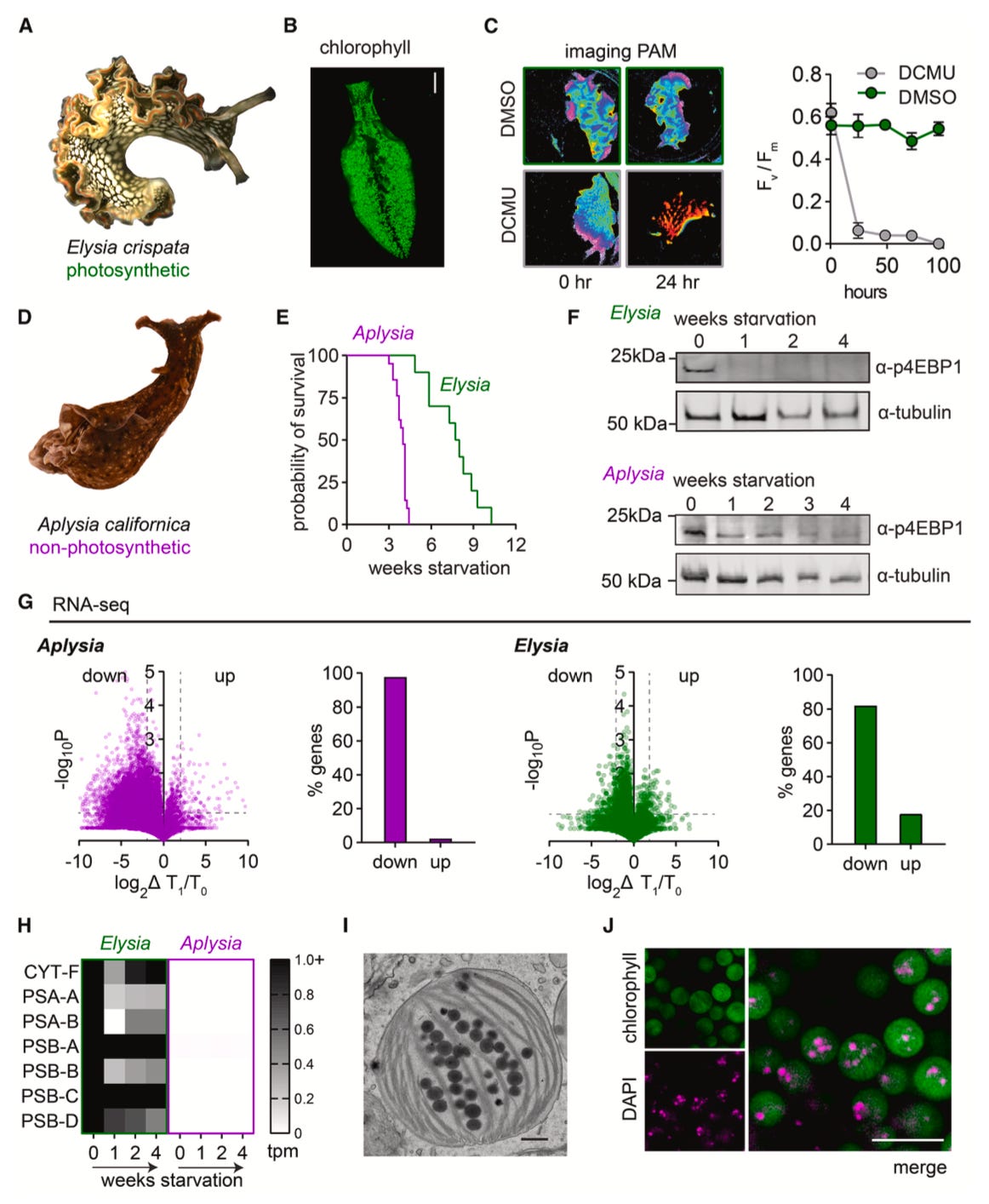

To answer these questions, the team first began by comparing Elysia’s ability to survive starvation to that of another sea slug called Aplysia, which does not harbor chloroplasts. They found that Elysia could outlast Aplysia by nearly three months, which led them to ask whether this was truly because of its chloroplasts. The team took advantage of a signaling pathway associated with metabolism called mTOR, responsible for regulating growth and survival, and assessed its activity in response to starvation in both slugs. Experiments revealed that both slugs inactivated mTOR about a week into the starvation period, indicating that both organisms are undergoing starvation at the same rate. To confirm these results, the researchers also used RNA sequencing–a technique that lets scientists look at what genes are being actively transcribed, or expressed, in an organism–and saw that both slugs were transcribing less genes overall about a week into starvation. Interestingly, though, they saw that Elysia showed high expression levels of photosynthesis genes originating from their chloroplasts. This observation led the authors to ask whether the slugs were instead using their own proteins to support chloroplast photosynthesis during starvation.

To test their hypothesis, the team used a technique called Click chemistry labeling to mark newly synthesized proteins in the slugs. After performing this labeling, they isolated the chloroplasts and analyzed their proteins, reasoning that if the slugs were providing proteins to these cells, they would see “contamination” of slug-originating proteins in the chloroplasts. Indeed, the vast majority of proteins they found belonged to Elysia. Not only that, additional analyses revealed that many of these proteins were actually associated with processes of phagocytosis or endocytosis–in other words, with processes that involve engulfing an object or bringing it into the cell. This observation gave rise to an intriguing question for the authors: are these slugs creating specialized organelles to house their chloroplasts?

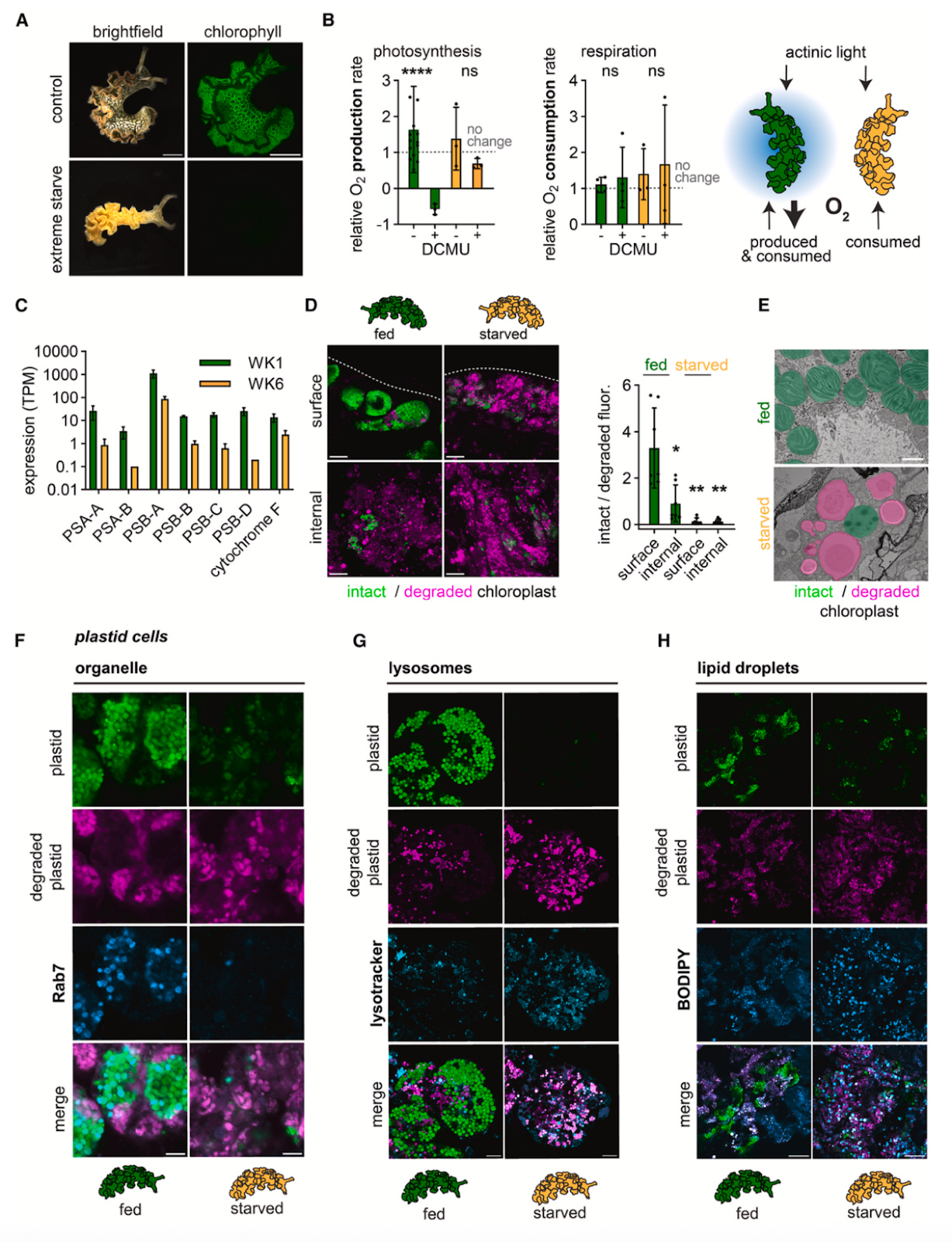

Returning to their analysis, the team observed that Rab7, a marker associated with phagocytosis, was the most abundant protein in the chloroplasts. For the authors, this abundance supported the idea that these cells may be contained within a structure akin to the vesicles, or membrane-enclosed sacs, which are responsible for importing materials into the cells. Taking a closer look at these chloroplasts using imaging and labeling techniques, the authors realized that they reside within specific cells inside the slug’s digestive tract, which they termed plastids. Additional experiments confirmed that each chloroplast was surrounded by a membrane–an expected observation if they really are being contained by an organelle–which also expressed markers associated with phagosomes. Together, these observations led the team to conclude that the chloroplasts were being contained within a structure they termed the “kleptosome,” a phagosome specialized for maintenance of chloroplasts.

The discovery of this kleptosome structure immediately raised two major questions for the authors: how do these structures establish an environment that supports chloroplast function, and how do they actually regulate chloroplast function in the first place? To get at these questions, the team first started by looking at electric signals in the membrane of the kleptosome to determine whether it was letting ions and other small molecules through. Their experiments revealed that this was not the case, leading them to wonder whether the chloroplasts themselves were providing the signals necessary to regulate the membrane instead. Since chloroplasts produce the energy molecule ATP, the team reasoned that this molecule may be involved with membrane regulation. Indeed, the team confirmed their hunch, observing that perturbations to an ATP-sensitive receptor caused issues with photosynthesis.

In the midst of their experiments, the authors noticed something even more odd: during extreme starvation, the lettuce slugs were turning orange, just like leaves do in the fall. Additional experiments on these slugs revealed that their chloroplasts were being degraded, leading the authors to question whether Elysia was somehow eating them as a last-ditch effort to survive. Using multiple imaging techniques, the team observed both the presence of chloroplasts in the digestive tract as well as their degradation, which led them to ask whether the cells were breaking down by themselves or being actively digested by the slugs. Using different markers, the scientists saw that these cells were no longer enriched for Rab7, the phagosome membrane marker, but instead expressed markers for lysosomes and lipids. This shift towards lysosomes, an organelle that degrades materials, suggested to the authors that controlling lysosome abundance could act as a mechanism that decides whether kleptosomes should prioritize chloroplast storage or degradation, an interesting avenue for future study.

To round out their study, the authors wanted to expand past their sea slug model and ask whether other organisms that participate in endosymbioses–namely cnidarians and corals–also evolved kleptosome-like structures. To do this, they returned to their phagosome marker Rab7 and used its expression, as well as that of the chloroplast pigment chlorophyll, to investigate this question in the coral Lobophytum sp. and the anemone Exaiptasia diaphana. Across all three organisms, they saw that healthy chloroplasts were devoid of any Rab7, whereas degraded chloroplasts began to express high levels of Rab7. These observations led the authors to hypothesize that, when chloroplasts are healthy and slugs are well-fed, the kleptosomes resemble early stage phagosomes and hold off attempts to digest or degrade their cargo. As starvation takes place, nutritional needs cause the slugs to degrade their chloroplasts, at which point the kleptosome fuses with lysosomes to break down the cells. The fact that this mechanism has evolved more than once across different organisms speaks to its utility as a means of developing and supporting endosymbioses.

The Takeaways

While they may not seem so enigmatic on the surface, there is still much we have left to understand about the lettuce slug and its stolen quarry. As Bellono and team note in their Cell study, how chloroplasts are maintained in the absence of their cellular environment and how slug and cell alike manage to create the ideal conditions for their function remain unknown. That being said, while researchers have only just begun to scratch the surface of understanding these complex endosymbioses, studies like these are showing that they may have more in common than we previously thought. That corals, anemones, and sea slugs have stumbled upon the same solution to the same problem creates a foundation from which to interrogate how these partnerships have uniquely changed over the course of evolution and led to the development of novel organelles. In doing so, we stand to learn not only more about our own evolutionary history, but also how biological complexity and novelty are driven by these partnerships.