Thoughts On... COVID Mis-Information (Part II: The Communication, or Lack of It)

In this follow-up to our first Thoughts On... post, we reflect on the rise of misinformation during the pandemic and how we can begin to ameliorate mistrust in science.

Introduction

Four years out from the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, conversations surrounding topics like masking, vaccination, and the effects of infection on long-term health remain as contentious as ever. Some insist that the pandemic is over, while others argue that it is still very much ongoing. Public health officials like Florida Surgeon General Dr. Ladopo are advocating for the halting of COVID-19 vaccines. How did we get here? Why were these issues so difficult to understand during the pandemic, and why are our discussions surrounding them so volatile four years later?

In this follow-up Thoughts On… post, we’ll rewind and reflect on how misinformation became so rampant during the pandemic, and what factors contributed to this whirlwind. Then, we’ll turn towards science communication efforts during the pandemic and discuss what happened to the scientists who did attempt to inform others. Lastly, we’ll end with a discussion on the dangers of politicizing science and some musings on how we can begin to attempt to ameliorate disinformation and mistrust in science.

Why did misinformation become so prominent during the pandemic?

When the pandemic first began, we knew very little about the virus. What was supposed to be a two or three-week quarantine stretched into months of staying at home and isolating from others. While we watched the numbers of infected continue to grow, scientists all over the world were working around the clock to understand the COVID-19 virus and figure out ways to keep us safe–whether through vaccines or developing public health guidelines.

When we think of science, many of us are tempted to think of it as a series of major discoveries and breakthroughs. However, the truth is that discoveries aren’t instantaneous “Eureka!” moments where our understanding of the world changes from one minute to the next. In reality, science builds up to these discoveries over time, with small-scale breakthroughs gradually leading to broader paradigm shifts. The pandemic turned that dynamic on its head, requiring scientists to communicate results as fast as possible, cobbling together a framework off of the latest data. Sometimes, data was contradictory, leading some to believe that science was failing us–and subsequently, that it didn’t deserve our trust. A particularly memorable example of this was Dr. Fauci’s initial claim that masking was not necessary, a view that later changed as the data continued to evolve, especially as it pertained to asymptomatic carriers. While disagreement and change does happen in science, these are usually insular situations that occur over years and decades within scientific circles–not over days and weeks under the public eye.

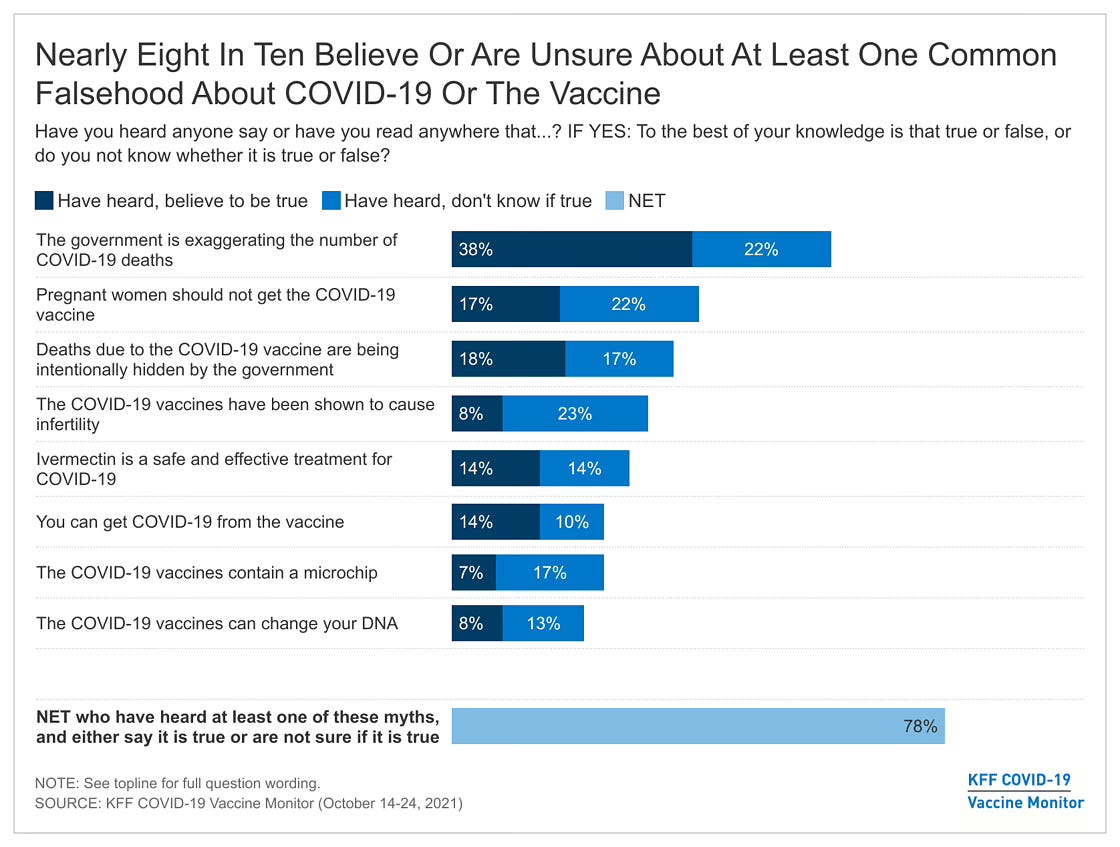

In addition to the rapid nature of scientific discovery and advancement during the pandemic, traditional media and social media platforms also played a role (whether intentional or unintentional) in the spread of mis- and disinformation. Regardless of the way one sought information during the pandemic, the likelihood of encountering misinformation was very common; a study published in 2021 by the health policy and research group KFF found that 78% of the general public either believed in or were unsure about at least one false statement associated with COVID-19.

While traditional news media is often considered to be objective and reliable, research shows that factors such as sensationalism and scientifically accurate reporting did vary between news media outlets during the pandemic. Interestingly, these factors appeared to have a correlation with the outlet’s political leanings. A study published in Nature’s Humanities and Social Sciences Communications journal in 2021 found that, across the U.S., Canada, and the UK, “overall scientific quality of news reporting and analysis was lowest on the populist-right of the political spectrum.” This analysis took into account the validity, precision, and context of the scientific reporting as well as whether proper fact-checking was undertaken. Additionally, these publications were found to have lower-than-average sensationalism, while publications that were more moderate or liberal-leaning were found to have somewhat increased sensationalism. However, while incidents of misreporting did occur, especially in the context of results associated with unverified preprints, these paled in comparison to the propagation of mis- and disinformation on social media.

Social media platforms were wholly unprepared for the onslaught of misinformation that the pandemic brought with it. Given that most platforms already struggle with content moderation and inefficient blocking and reporting functions, these virtual arenas were primed to inadvertently assist with the promotion of false information–without an efficient way of filtering or removing this content. A study performed by The Integrity Institute in 2022, for example, found that algorithms and virality mechanisms on platforms like Twitter/X, TikTok, and Facebook amplify strategically crafted misinformation posts. Additionally, the ease of re-sharing on these platforms allows for misinformation to propagate quickly and reach a wider range of people, especially if their feeds are already attuned to that kind of post. This, in turn, enables widespread harassment that can go unchecked; a Pew Research Center study from 2021 on the state of online harassment found that a quarter of Americans had experienced severe abuse online, with 75% of these victims reporting that the abuse had occurred on social media. While some platforms have started to address these issues through community fact-checking–take Twitter/X’s “Community Notes” feature, for example, which was launched in 2021–there is still far more that is needed to both combat disinformation and prevent harassment, especially as it pertains to the scientists who are braving these issues to communicate with the public.

Science communication may have failed us, but we also failed scientists

While the process of communicating the scientific process underlying COVID-19 studies and vaccine trials suffered under the weight of public perception and misinformation, there were public health figures and scientists attempting to battle these factors and provide the public with a clearer picture of what was going on. Unfortunately, however, political polarization, in combination with misinformation, only served to put these figures in harm’s way–and possibly preclude them from speaking to the public again.

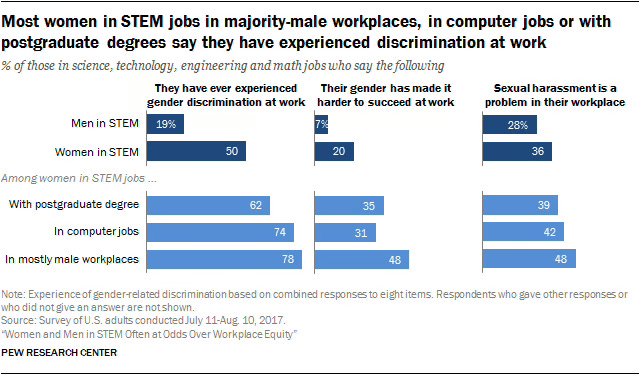

An article published by Nature Medicine in 2021 did a deep-dive on a few of these scientists and their experiences in attempting to confront misinformation during the pandemic. For example, when a Brazilian scientist studying chloroquine found that the drug had no health benefit for infected patients, he was forced to hire bodyguards as he came under intense scrutiny from all levels of society, including the government. Another scientist, a virologist who took to Twitter/X to critique preprint studies she considered troublesome, was repeatedly met with a range of attacks, ranging from minor insults to suggestions of violence or sexual assault against her. This case in particular raises another important factor to consider when it comes to scientists in the public eye: some individuals are more vulnerable than others. A 2018 study by Pew Research Center found that 50% of women in STEM jobs reported experiencing discrimination. Additionally, 62% of Black respondents reported discrimination in a STEM workplace, along with 44% of Asians and 42% of Hispanics. Beyond the workplace, abuse on social media platforms is more commonly experienced by those in under-represented groups, making these scientists vulnerable both in their research and their communication of it.

Here, then, we have a vicious feedback loop: of the scientists who do attempt to reach out to the public, harassment on social media and lack of regulation on the platform drives them off, discouraging both those scientists and up-and-comers from interacting with the public. Over time, we lose scientist involvement in public discourse, a loss that in turn enables an increase in the mis- and disinformation claims made and propagated by non-experts, particularly those with ulterior motives.

Why it’s dangerous to politicize science

When figures like Dr. Ladapo or Governor Ron DeSantis parrot misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine, they are directly putting their constituents at risk. There is a concept in medicine termed informed consent that is particularly relevant here. In essence, informed consent is the principle that a patient must be educated by their healthcare provider in all the risks, benefits, and alternatives of a given treatment or procedure. Once the patient has been properly informed of all of their options, they can then proceed to select the option that best suits them, taking into account all of their own concerns and beliefs. For a public health official, particularly one with a medical background, to mislead their constituents is a violation of the ethics of both their training and their position. By politicizing science, officials are preventing the public from receiving the resources they need to make informed decisions about their personal health and that of their community.

While this is concerning for multiple reasons, the most worrying of them is the effect it could have on national prioritization of scientific and medical research. The use of disinformation tactics will not only lead to a decrease in trust in our scientific institutions, but could have significant negative long-term effects on the state of science in our country. This could manifest itself in multiple ways, from decreasing funding for research to increased polarization between scientists and the public, all of which ultimately weaken our scientific and medical institutions. While this may not seem like a drastic issue right now, it will certainly become one with time, especially when we consider the possibility of another future pandemic or crisis. Already, lack of funding is impeding data collection of COVID-19 infection levels on local, state, and national levels–a concerning issue given the recent emergence of a new Omicron subvariant, JN.1. Concern is also being raised on a global scale; for example, the World Economic Forum ranked misinformation as one of the greatest threats to humanity in their Global Risk Report last month, a testament to how widespread the issue–and its consequences–are becoming.

Regardless of your own personal political beliefs, I think we can all agree that attempting to limit the public’s understanding of a disease that could have significant long-term impacts on their health works directly against the nation’s best interests. You should not have to be a scientist or have a medical background in order to have access to up-to-date and accurate information regarding COVID-19 and possible immunization and treatment options. If politicians and officials are inserting themselves into scientific circles and attempting to dictate what is true and what is not, it is the responsibility of scientists to assert their authority and speak out against these individuals. As scientists, and as a public, we are not in a position where we can afford to be passive on these issues–we must speak up, and we must speak up now. However, given the fraught relationship between scientists and the general public, how can scientists best re-initiate efforts to connect with the public?

Scientists, how can we begin to rectify this mistrust?

While it will take time to fully understand the scope of the present disconnect between scientists and the public, if scientists can ever hope of regaining that trust, we must begin to mitigate disinformation and attempts to politicize science. We are not in a position to ignore the increasing politicization of science, especially given the upcoming presidential election and the consequences it could have for scientific funding and researcher protection. We need to reach out to the public and meet people where they are–not where we want them to be.

As scientists, we undergo so much specialized training that it can be easy to forget how hard it was to understand concepts we now consider elementary. Not only that, but it can be difficult to learn how to explain these concepts to an audience that does not have the same level of training or understanding, especially when it’s not a skill we are taught in our formal training. This can lead scientists to withdraw from more public-interfacing circles and isolate themselves within their intellectual communities. It can also lead some scientists to consider themselves above the public, leading to a more adversarial relationship with scientific communication and outreach. However, the fact of the matter is that if we put ourselves on a pedestal, we run the risk of never coming down from it. We cannot isolate ourselves from the rest of the world and hope that one day, those who disagree with us will see reason. Instead, we must go to them.

Seeing the issue in its entirety, you may be thinking: It just isn’t going to be possible, or, there’s no point in doing this. It’s true that repairing our relationship with the public is going to be an uphill battle. We aren’t usually given the requisite training for interfacing with the public and given the current state of abuse on social media platforms, it may not always be safe for us to do so. However, instead of viewing this as an impediment to our involvement, I suggest we view it as a motivation to create the tools necessary to enable us to engage with the public. For example, we can advocate for researcher safety measures at our universities and institutions that can protect scientists against abuse faced on social media. We can also initiate efforts to develop a formal scientific communication curriculum for undergraduate and graduate students in the sciences. Additionally, we can continue to advocate for the inclusion of science communication in professional development opportunities, as well as the inclusion of experiential opportunities during graduate and postdoctoral training. Importantly, we should also reach out to the public and ask them what they would like to see from us, both in terms of forms of communication and content.

What can the public do?

While there is plenty to be done on the science side of things, we will need the efforts of the public to truly turn the tide of scientific mistrust. The good news is that there is plenty of action to be taken. One of the most important things you can do as a member of public is to support science journalism. The past year saw a striking amount of layoffs in science journalism, as well as the shuttering of multiple impactful science publications, including the 151-year old magazine Popular Science. As one of the most standardized forms of science communication, the loss of science journalism jobs and publications is a worrying omen for the field. Quite simply, if you want to hear from scientists, you need to let them know! Subscribe to the coverage and commentary of major magazines like Science or National Geographic, or support homegrown blogs and newsletters like this one.

If you’d prefer to interact with scientists more directly, you can easily reach us on social media platforms. While a good portion of the Science Twitter/X community has left for other platforms, you can continue to find high-profile scientists and science communicators like Dr. Raven Baxter (@ravenscimaven) interacting with the public. Additionally, if you’re willing to try out a new platform, Bluesky has a number of science feeds that you can add to your main feed. Beyond the screen, check out your local universities or scientific institutions and see if they have public lectures or events that you can attend. For example, UF’s Whitney Laboratory in Marineland hosts “Evenings at Whitney,” where members of the public can attend scientific talks. Additionally, national organizations like Astro On Tap host events all over the country that encourage science communication in more casual non-academic settings.

Lastly, don’t forget the power of your voice and your vote! If you care about funding science or if there’s a scientific initiative you’re particularly excited about, reach out to your representatives in Congress and let them know. The same applies for your state and local governments. Outside of that, there’s plenty you can do depending on your comfort and ability. You can attend town halls, spread the word about an initiative or bill on social media, or even organize around a particular issue and get your community involved.

The bottom line

These issues will not have a one-size-fits-all solution, but it is only through entering into dialogue with scientists and non-scientists alike that we will be able to overcome the obstacles that prevent us from understanding each other. As scientists know, we make the most progress when we tackle problems as a community. We are rapidly approaching a turning point that may decide the fate of science in our country for years, if not decades, to come. Let’s work together to ensure a future where all of us can be a part of science.