What It Would Mean To Lose The National Science Foundation

In a companion piece to our previous article on the NIH, we discuss the importance of the National Science Foundation (NSF) and how the agency is currently being affected by political interference.

Introduction

In our previous post What It Would Mean To Lose The National Institutes of Health, we took a deep dive into the National Institutes of Health (NIH), providing context not only about the role it plays in the U.S. biomedical system, but also how current political interference is preventing it from successfully carrying out its life-saving work. While the importance of the NIH and its contributions cannot be overstated, it is not the only federal agency that plays a key role in funding and supporting American research. Its lesser-known counterpart, the National Science Foundation (NSF) accounts for a quarter of all federal funding put towards supporting scientific research at universities and research institutions across the country. Importantly, NSF supports the basic sciences and engineering fields whose work may not fit the scope of biomedically-focused agencies like the NIH.

Though the NIH is undoubtedly the largest source of funding for biomedical research, the NSF fulfills an important role by funding the basic sciences: it supports the research that helps create the foundation for our understanding of different phenomena, from how butterflies pattern their wings to how galaxies form, which can later be applied in other contexts like biomedical research (take the recent example of how studying lizard venom led to the development of GLP-1s like Ozempic). As we’ll see, NSF funding has played a role in helping create and support many technologies that have become a part of our daily life (including, but not limited to, the internet!). We’ll also see how recent actions from the current political administration are jeopardizing research funding and training opportunities across the nation–in addition to the agency itself.

What is the NSF?

Before we get into the details, let’s start with the basics. The National Science Foundation is a federal agency created by an act of Congress in 1950–making it a relatively young agency compared to others like the NIH. According to the act, NSF was founded to, among many things, initiate and support basic science research, to award graduate fellowships, and to foster interchange of scientific information between the U.S. and other countries. Today, 75 years since the passing of this act, the National Science Foundation is a crucial part of the U.S. research ecosystem and has contributed to significant advances that have shaped not only science itself, but that of our daily lives.

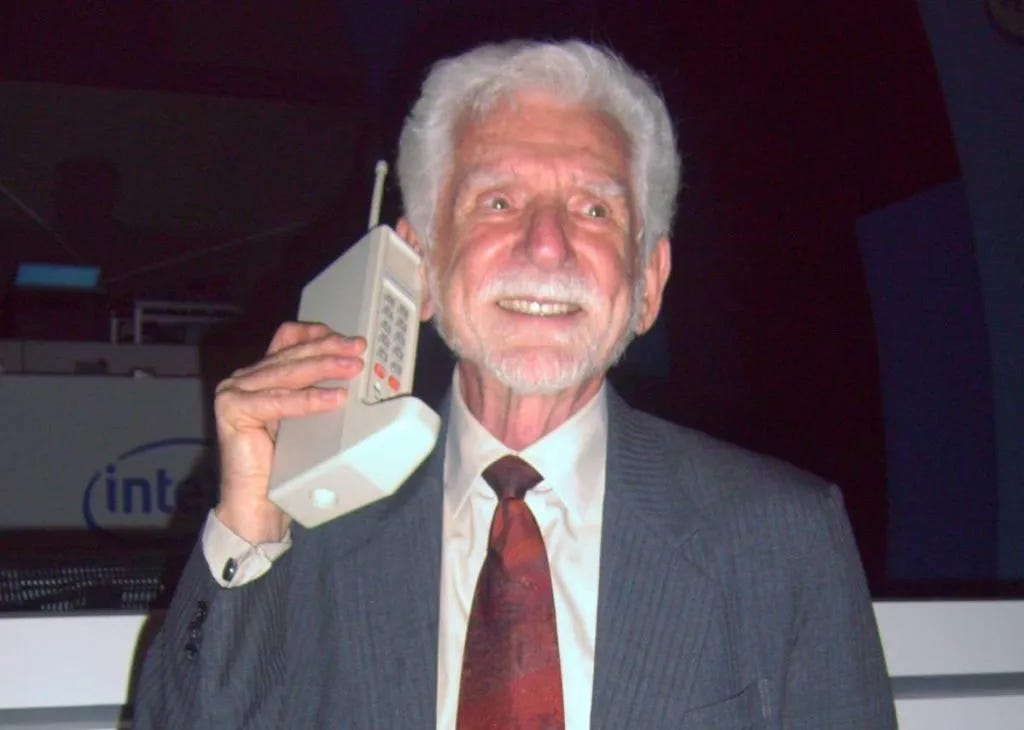

Don’t believe me? If you’re reading this article on your smartphone, or using the internet to access it, you have the NSF to thank for that. The touch screen that you use to navigate through your phone and the lithium-ion battery that powers it are both products of the agency’s investment as far back as the 1970s. Take a minute to think about that. In the 70s, the concept of a handheld phone was just becoming a reality; a phone that fit in the palm of your hand with a screen you could touch was still decades away. And yet, despite that, the NSF was already funding studies exploring the technology that would eventually give rise to the smartphones we know today. This is why funding basic research is so important: while the applications may be far off in the future, the knowledge they create is vital towards eventually reaching them.

This pattern holds true in a multitude of contexts, and has even led to innovations and advances in areas of science not typically supported by NSF’s scope. Back in 1964, microbiologist Tom Brock received a grant from the agency to study how life works at high temperatures, a question that took him to Yellowstone’s hot springs in search of extremophiles. There, he and his student discovered a bacteria they called Thermus aquaticus, which had enzymes that could work at incredibly high temperatures. Two decades later, this discovery paved the way for the development of a technique called polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, which uses the heat-resistant enzyme Taq polymerase to massively amplify genetic material. If that sounds familiar, it’s probably because you heard about it during the pandemic in relation to COVID testing; PCR helped us achieve more sensitive and accurate reads on whether a person had COVID or not by amplifying any existing viral fragments. Outside of that, though, PCR is a mainstay of modern biology, and can be used to achieve many different functions. Again, think about this: a scientist curious about how organisms survive extreme environments in the 60s laid the foundation for a tool that would become universally used in research–to the point that it would help us navigate a pandemic nearly 60 years later. This is the power of basic research, and this is precisely the kind of work that NSF has been supporting for its 75 years.

NSF Funding & Its Relationship To The Economy

Much like the NIH’s institutes and centers, the NSF is divided into eight main directorates that span multiple scientific fields, including but not limited to the biological sciences, the geosciences, engineering, the social sciences, and education. Each directorate has multiple divisions dedicated to specific subfields, adding up to a total of 37 divisions across the directorates. Each directorate offers its own funding programs and opportunities relevant to its specialities, collaborations, and goals. Importantly, these funding opportunities are highly competitive, with proposals undergoing an elaborate process of review in order to be accepted. Of all of the applications it receives in a given year, NSF funds only about a quarter of them, a percentage that indicates just how rigorous the agency is in deciding what research to fund.

How exactly does this funding work? Just like the NIH, NSF is appropriated money from the federal budget by Congress. This past fiscal year, the agency was appropriated $9.06 billion, making up 0.1% of the overall federal budget. The majority of this funding–about 7 billion–goes towards supporting research across the country, another billion goes towards supporting STEM education, and the rest is distributed throughout other offices within the agency such as the Major Research Equipment and Facilities Construction, which supports the commissioning and development of the infrastructure needed to perform research (think research facilities or specialized equipment). As we’ve discussed in What It Would Mean To Lose the National Institutes of Health, this funding translates into major economic activity. The Federal Reserve recently estimated that, since the end of World War II, non-defense related federal investment in research has generated an economic return of 150 to 300%, which you can think about as 1.50 to 3 dollars returned for every dollar invested. And, as we’ve also discussed in our NIH piece, cuts to research funding can result in significant economic losses. Already, estimates based on next year’s fiscal budget (which we’ll get into in the next section) indicate that the U.S. economy will lose around 10 billion annually from cuts to the NIH and NSF alone.

Clearly, funding from the NSF plays an important role in supporting not only our nation’s basic research, but also our nation’s economy. That being said, increasing political interference is setting a concerning precedent for the agency’s ability to continue playing that role.

Grantsmanship & NSF Funding

Let’s start with recent grant cancellations and their effects on research funding nationwide. Back in April, the Trump administration began canceling grants outright in keeping with an executive order targeting DEI efforts, starting with 400 cancellations on the 18th and eventually reaching over 1000 cancellations by the 25th. Of the grants targeted, many were focused on research meant to improve science education and support trainees early in their scientific careers. Not only that, these cancellations also targeted research focused on mis- and disinformation, a concerning development given how prevalent these forces are and how easily propagated they can be. And, as we saw with NIH’s Board of Scientific Counselors, these terminations have disproportionately targeted women and underrepresented minorities, with women PIs making up 58% of all terminated grants despite only representing 34% of all women PIs on active grants. In addition to complete cancellation of existing grants, the agency was ordered to “stop awarding all funding actions until further notice” on April 30th, effectively preventing both new and existing research programs from moving forward.

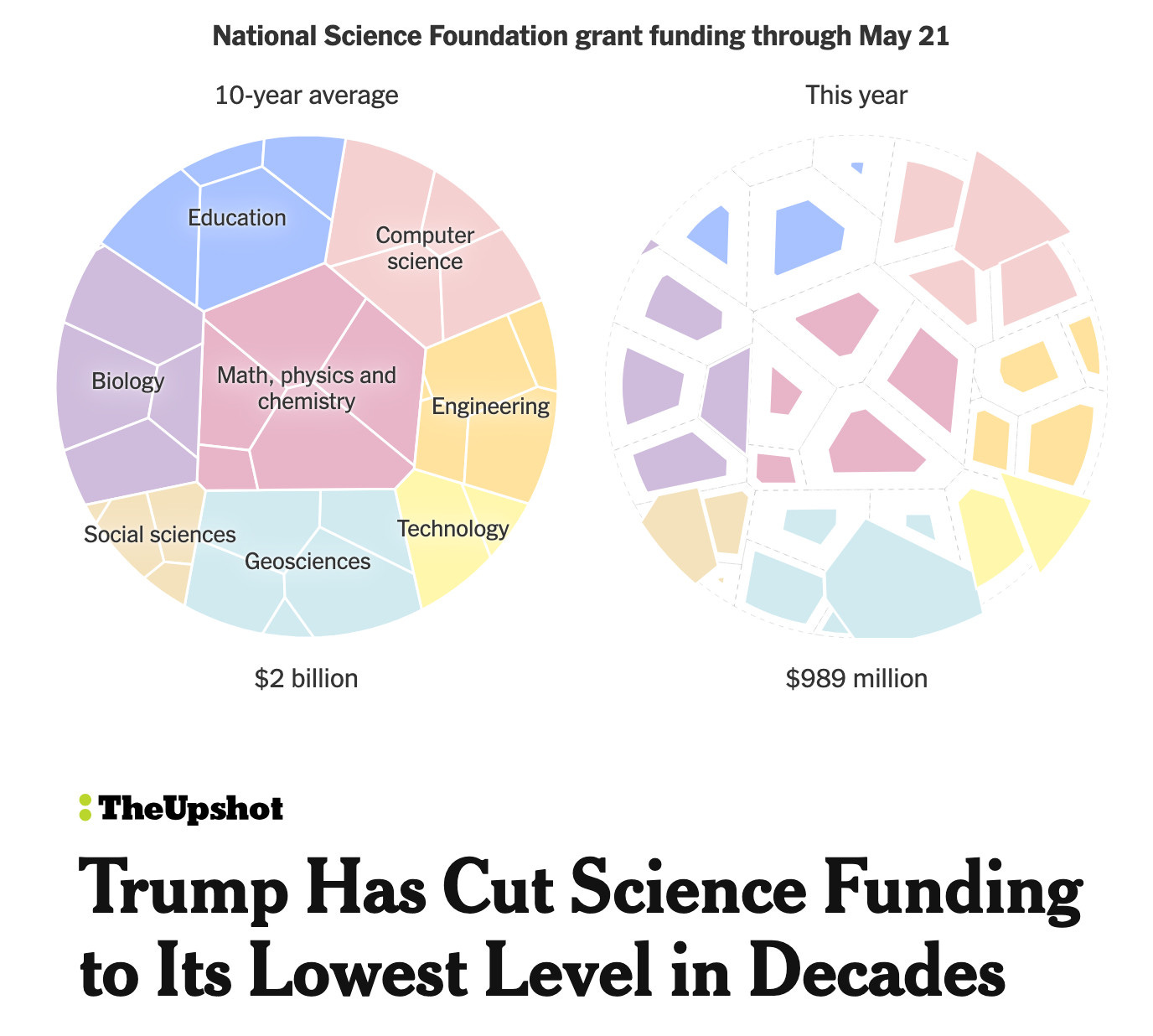

Cuts have continued to take place throughout the months of May and June, with estimates indicating that over 1600 grants have been cancelled and 1.5 billion in funding has been lost. Additionally, the recipients of these grants have been told that they cannot appeal these decisions despite the fact that NSF has an appeal process in place for these cases. To see how the different directorates have been affected by these cuts, take a look at the schematic below, which visually shows the reductions in the major subject areas of the NSF. It can’t be overstated–this kind of direct interference from the White House is unprecedented and represents a complete overreach of congressionally appropriated funding.

Unfortunately, recent developments suggest that things won’t be getting better anytime soon, either. Just a couple of weeks ago, the Trump administration released its budget request for the upcoming fiscal year, leaving scientists shocked by the cuts requested. In terms of the NSF specifically, the administration requested a 57% reduction in funding, taking it from its current $9 billion down to $3.9 billion. Remember, the agency funds a quarter of all STEM research in the United States; now, it’s being expected to do the same with less than half of its usual funding. That translates to only 7% of recipients receiving grants as opposed to the already selective 26% we mentioned earlier. These cuts are also targeted, with the education, physics & mathematics, and geosciences directorates being the hardest hit. Additionally, certain areas of focus, like clean-energy research, are being almost completely eliminated in response to the administration’s ideological priorities.

Of course, this is only a request–Congress does not necessarily need to abide by these recommendations to the letter. That being said, the precedent set by this budget is incredibly concerning and serves as a clear indication that these attacks will not be subsiding in the near future.

Training & Science Education

In addition to supporting basic science research, the NSF also plays an indispensable role in training our nation’s future scientists. In this piece, we’ll be focusing only on two of its flagship programs–Research Experiences for Undergraduates (also known as REUs) and the Graduate Research Fellowship Program (GRFP). Founded in 1987, the former of these two focuses on supporting undergraduates by providing them with valuable research experience. NSF funds these programs at a wide range of universities and research institutes across the country, each with a particular specialty or subtopic. Once there, students can engage in original, mentored research in addition to receiving opportunities for professional development, science communication, you name it. For many students, an REU may be their first exposure to performing scientific research and can set the trajectory of their future interests and goals.

I say this not only because it’s true, but because it was my own experience. The summer between my sophomore and junior year, I participated in an REU at the University of Florida’s Whitney Lab for Marine Biosciences. At the time, I was really interested not only in working with marine organisms, but also in studying the phenomenon of regeneration, which I hadn’t had the opportunity to pursue before. That summer, I got to do just that, in addition to presentations, classes, and exploring what a career in science is like. If someone asked me to identify a defining point for the rest of my career, I would choose my summer at Whitney without a moment’s hesitation. There, I learned that I really could be a developmental biologist, and I identified the research interests that would eventually lead me to my undergraduate thesis research and my graduate program. And, trust me, my story is but one of many. This program is incredibly important–not just for its ability to expose our future scientists to what it’s like to pursue this career, but also in giving them the opportunity in the first place, something they may not have access to in their own communities or institutions.

Sadly, earlier this year, several institutions were forced to cancel their REU programs after not receiving funding renewals or accepted REU proposals from NSF. No reasoning was given, but experts at the time assumed that expected funding cuts (which, as we’ve just seen, have definitely come into play) were causing the agency to save funds where it could. As a matter of perspective, NSF spends around 80 to 90 million annually on its REU programs, amounting to only 1% of its yearly budget. While the financial aspect was surely a factor in these decisions, it shouldn’t go unsaid that REUs play a significant role in giving opportunities to students from underrepresented backgrounds–which would likely make the program a prime target for the administration as well. However you spin it, though, these initial cancellations mark a huge loss for science across the board and spell a worrying future for our young scientists.

While REUs give students their first taste of scientific research, the NSF GRFP, on the other hand, acts as the cornerstone of their scientific training. Beginning in 1952, this fellowship program has provided financial and professional support for students pursuing graduate degrees in the natural sciences, social sciences, and engineering. More specifically, students are awarded a graduate stipend in addition to discretionary funds that can be used for a variety of professional development and training opportunities. For many students, this is a transformative award–directly funding their Ph.D. research and supporting the trajectory of their future careers. The financial security provided by this award shouldn’t be underestimated, either; for some students, it can be the difference between pursuing their Ph.D. or not. It can also determine what kind of research question a student can pursue; if a lab doesn’t have the funding to support the student’s project, independent funding can make sure that the student has the means to pursue the research question they’re most interested in.

As we saw with NSF’s REUs, however, this program is similarly at risk. Usually, the NSF awards around 2,000 fellowships a year. This April, however, the scientific community was shocked to see the number of fellowships cut in half, with only 1000 awarded overall. Additionally, honorable mentions, a designation that recognizes talented applicants but does not confer a monetary award, doubled, leading some to speculate whether these students would have won the award under normal circumstances. Indeed, the NSF recently awarded an additional 500 awards to applicants who had received honorable mentions, indicating that interference with the budget may have prevented the agency from initially granting the expected amount of fellowships. Regardless, this cut in fellowships represents a significant lost source of independent funding, putting students in a more difficult position when it comes to securing funding for their research. While the agency is considering partnering with private and philanthropic groups to make up for the shortfall and grant more awards to students on the honorable mention list, the precedent set by these cuts suggest that it will only become more difficult to pursue graduate studies in the sciences.

In addition to supporting scientific training in the United States, NSF is also deeply involved in supporting STEM education and programming across the country. Funding from the agency has made significant contributions to informal STEM programming in schools, museums, and, even, your TV: several popular STEM education programs directed at children–think Bill Nye the Science Guy, The Magic School Bus, and Cyberchase–were created with help from the NSF. This highlights the important role that the agency plays not only in supporting scientific research, but in creating the next generation of scientists through communication and outreach geared at young children. In other words, NSF is involved in every bit of the scientific pipeline, from initial exposure to science to a professional research career, making the administration’s actions toward the agency particularly concerning for the future of science in the United States.

As we mentioned earlier, the education directorate took one of the hardest hits in the Trump administration’s proposed budget, with a 75% suggested reduction in funding. If you look back at the diagram showing how different sections of the NSF have been affected by funding cuts, you’ll also notice that education has suffered the most loss so far–accounting for over 50% of all cancelled grants. Let’s take a minute to reflect on what this means. The education directorate performs research that accomplishes everything from understanding how to better teach the sciences to finding ways to include everyone in our nation’s science. If we look at the big picture, things look pretty grim: not only are we losing opportunities for students to perform research and undertake graduate studies in the sciences, we’re losing the very resources that get them interested in science and allow them to learn about the world around us.

Usually, when scientists talk about the phenomenon of brain drain, we’re referring to American scientists packing up shop and taking their science to other countries. However, with everything happening, it’s becoming more and more apparent that we should be thinking about brain drain in terms of losing an entire generation of scientists not to other countries–but from science completely.

Layoffs & Restructuring

Before we delve into the layoffs and restructuring that has taken place at the NSF, let’s briefly backtrack to February of this year. As we shared in Science Under Attack, the agency suffered major layoffs alongside other federal agencies like the NIH, CDC, and FDA, losing 10% of its entire workforce. Of those laid off, many were involved with helping applicants navigate the grant application process, creating a roadblock towards appropriation of funding.

Unfortunately, these layoffs were just the start: back in May, staff received a memo from NSF’s chief management officer announcing both a major restructuring of the agency as well as an additional reduction-in-force (also referred to as RIFs). The restructuring would eliminate all 37 divisions from the eight directorates, in addition to the executives who directed them. It would also eliminate the agency’s Division of Equity for Excellence in STEM. Additionally, both staff from NSF’s temporary workforce (experts that advise NSF on research priorities) and its supervisory Senior Executive Service would be let go. And, if this were not enough, restructuring would also bring with it a new grant vetting system dependent on the administration’s ideological leanings, extending political control over who and what gets funded. While this restructuring has been paused by a court order, the precedent set by this attempt does not bode well for the agency’s future.

Before the chaos incited by the restructuring, however, the agency was already struggling through a transition of leadership. At the end of April, then director of the NSF, Dr. Sethuraman Panchanathan, resigned from his position. Originally nominated to lead NSF by President Trump in 2019, Panchanathan terminated his six-year tenure early, writing to the agency that “I believe that I have done all I can to advance the mission of the agency and feel that it is time to pass the baton to new leadership.” While the reasoning for his exit was unclear at the time, sources speculated that, between the administration’s interference (by this point, the agency was beginning to terminate grants, seemingly triggered by DOGE’s presence at NSF) and the difficult balancing act of portraying a thriving NSF in the face of so many losses, Panchanathan was driven to resignation. He’s not the only official to step away from NSF in response to these attacks, either–Dr. Alondra Nelson, a member of the NSF’s advisory body known as The National Science Board, resigned from her position in the hopes of drawing attention to just how severe the situation was becoming.

Taken together, these developments all point to an increasingly concerning picture: the erosion of our nation’s science. The NSF is not only being restricted in its support of basic research–whether that be in what research it gets to fund or how much funding it is appropriated by the government–it’s being dismantled from the inside out. If things continue as they are, the agency will no longer be able to effectively maintain its role as a supporter of our nation’s science and all the things that support entails, like giving rise to our next generation of scientists or contributing to our economy. These are not things we can afford to lose. But what can we do about it?

Conclusion

Grant cancellations, massive hits to essential training programs, a complete restructuring of the NSF, and a major loss to the agency’s budget. You may be wondering: where does this leave us? First, let’s start with the fact that the fight isn’t over yet. In the past weeks, scientists have spoken out about the changes taking place at the NSF and the harm they will cause to U.S. science. In response to the proposed budget changes to the agency, 13 former high-level NSF officials–including former directors of the agency–wrote to the White House in protest of their suggested changes. Scientists from all over the nation have also written to express their concerns about the dissolution of the directorate advisory committees we discussed earlier. This kind of awareness-building is necessary, important, and must continue if scientists wish to successfully inform politicians and the public alike as to the gravity of these changes.

This is a baton we ourselves must take up, however, if we wish to see change happen. As we discussed in our previous post on the NIH, the most important things we can do right now are to spread the word about what’s happening and to make our voices heard.

Inform others. If you weren’t familiar with what NSF does (or even what it is) before reading this post, it’s pretty likely that your friends, family, and loved ones may not be, either. Everything from touch screens, to the internet, to the enzyme that makes PCR reactions possible, to some of your favorite childhood TV shows are products of NSF’s investment in the future of science and the future of our country. Share these stories with your community and tell them about how basic research has laid the foundations for the lives we experience today. If you’ve benefited from NSF’s training programs, like the GRFP or its REUs, consider sharing your story on social media platforms through NSF’s Science Happens Here initiative or even in your local newspaper through initiatives like the McClintock letters. Additionally, we must continue to document and draw attention to the research we are losing through grant cancellations. If you want to see what grants have been cancelled at your institutions or within your state, or if you would like to report a grant cancellation of your own, Grant Watch allows you to do both. The more awareness we can create of the importance of the NSF, the more effective our response to the administration’s current actions will be.

Make your voice heard. Of everything that’s on the horizon for NSF, the most immediately concerning is the proposed cuts to its budget. However, while these numbers are a cause for concern, remember: they are not set in stone. If you do not agree with the changes that are taking place, let your representatives know. If you’re not sure how to do so, you can use tools like 5calls or Save NSF’s Take Action page to get in contact with your respective congressperson and communicate your concerns. You can also consider volunteering with or donating to organizations like Stand Up For Science to help the scientific community reach the public and increase public support for these issues.

This isn’t the way this has to be, but it will become our reality if we don’t do everything we can to fight it. This is the moment to take a stand and defend our scientists, our research, and our nation’s future–and to do it together.